The Da Vinci Curse by Leonardo Lospennato

Jan 14, 2020

7 mins

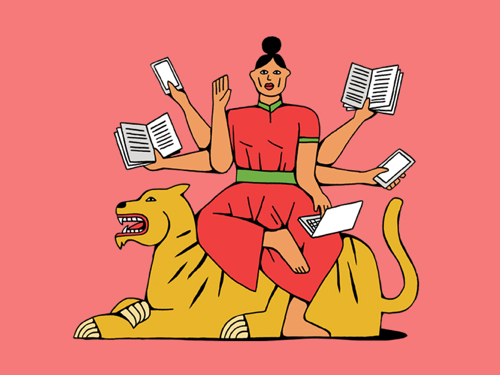

Our episode 8 will be of interest to all the “multipotentialites” out there. The Da Vinci Curse provides a life design guide for people “with too many interests and talents”. In a world that offers unprecedented access to knowledge, education and art, more and more people are struggling with the agony of choice when it comes to finding and sticking to a project, a hobby or a job. While some people succeed in actually mastering several different disciplines over their lifetime, others just waste their time trying too many things and accomplish nothing.

Multipotentialism is seen as an increasingly widespread trait among talented millennials (and not just millennials), so HR people looking to recruit, retain or manage talented employees ought to be familiar with the concept and understand the inner workings of those struggling with the agony of too many choices. Because the professional world still belongs to the specialists, multi-talented generalists often find it hard to leverage their multiple talents and interests in the professional world.

Leonardo Lospennato—his name must have predisposed him to a strong interest in Leonardo Da Vinci!—is a self-proclaimed “Da Vinci Cursed” (DVC), a multipotentialite struggling to make the most of his too many interests. A computer engineer by trade, he became a guitar maker, magazine editor and author. He wrote The Da Vinci Curse in 2012 to help fellow DVCs make the most of their “curse”. His book offers precious advice on how to choose activities, find a professional mission and get one’s priorities straight. It can also help HR professionals work with the multiple talents they are responsible for.

“Inconstancy is the dark companion of those who try to follow too many roads at once”.

“Time is the scarce resource par excellence. Money comes and goes, love comes and goes, and luck comes and goes. But time just goes away.”

- Leonardo Lospennato in The Da Vinci Curse.

What is the Da Vinci Curse?

The symptoms described by Lospennato seem very familiar to many of us and are increasingly common: multiple (sometimes contradictory) interests, bursts of enthusiasm that soon fade, and the feeling that we are not really accomplishing anything . People with multiple interests and talents often think they need to “grow up” and find their “true calling”—that is, some profession that they can stick with for the rest of their lives. Of course they rarely find it and blame themselves for failing to do so.

The phrase “Da Vinci Curse” is Lospennato’s own invention. It refers to what is now commonly known as “multipotentialism”, a concept popularised by Emily Wapnick’s renowned TED talk. Da Vinci, among other Renaissance men, is often cited as the ultimate “multipotentiate” or polymath (“a person whose expertise spans a large number of different subjects” -Wikipedia). Polymaths like Da Vinci can draw on complex and varied bodies of knowledge to solve problems. And they are able to develop valuable intersections between different bodies of knowledge.

Most great men from the Renaissance and Enlightenment excelled at several fields in science and the arts. Da Vinci’s areas of interest included: painting, sculpting, architecture, music, science, mathematics, engineering, geology, poetry, literature, cartography, etc. He has been called the father of paleontology and has also been credited with many inventions, among which the helicopter.

Today’s DVCs (“Da Vinci Cursed”) are enthusiastic individuals who love all kinds of things, have a developed aesthetic sensibility (they often enjoy art and music), enjoy a lot of hobbies and have changed careers more than once over the course of their professional lives. They are increasingly common. “In ancient times no one but a privileged few could write and read; nowadays, anyone living in the free world can google up anything she wants”.

Why being a DVC is often a problem

First, in a world where options are plentiful, information is overly abundant and stimulating activities are inexhaustible, being a DVC is not always a blessing. The more options you have, the harder it is to choose and the more often you will just lose time and remain shallow. DVCs often struggle with inconstancy, frustration and dissatisfaction. They drift from one activity to the next without accomplishing much. Their hyperactivity often turns into attention deficit disorder. They sometimes suffer from depression too.

Secondly, the professional world overwhelmingly rewards the specialists. In Da Vinci’s time, those with wider knowledge could lead and become the powerful servants of kings and princes. Today, only the super specialised can hope to achieve professional recognition. “The volume of the world’s data doubles every few years”. Therefore, being very specific is the only chance of being original. There is no place for “know-it-alls” (whose knowledge is shallow). Up until quite recently, DVCs could look to managerial positions to make use of several of their multiple talents, but today even those positions are filled by specialists (management specialists).

When it comes to the search for meaning, DVCs are trailblazers

But the frustration and dissatisfaction that DVCs experience are essential because they trigger a search for meaning, which is critical to our mental health. “The search for meaning may arouse inner tension rather than equilibrium. However precisely such tension is an indispensable prerequisite of mental health”. And DVCs devote a lot of energy to searching for meaning in action.

It is in action that the search for meaning is most relevant. As Victor Frankl, psychiatrist and holocaust survivor, wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning: “The question about the meaning of life must be reconstrued not as a question, but as an answer expressed in a realm that transcends language: action”. The answer lies in life itself: experiencing beauty and goodness, finding love, creating work and deed, and when suffering, challenging oneself to change. Meaning can’t be “found” in one’s life, it must be given to one’s life! That’s what actualisation and individuation are all about. And that’s what DVCs strive to do all the time…(even if they rarely succeed).

The path to self-knowledge is the path to individuation—the integration of a fragmented, conflicting self into a functioning stable whole. Psychologist Abraham Maslow referred to individuation as as self-actualisation: “the desire for self-fulfillment; namely, the tendency for the individual to become actualised in what he is potentially”, the desire to become everything one is capable of becoming. So really, being a DVC is a powerful advantage when it comes to having that desire and trying to find answers in action.

To be or not to be YOU

A lot of people go through a time in their lives when they face an existential drama. It’s usually called a “midlife crisis”, although it doesn’t always occur at age 40. It is an inflection point that feels like a change or die situation, a point in time when one wishes to drop the mask and start the path to individuation: “there is but one success: to be able to spend your life in your own way”.

But individuation is more a process of gradual development than a single event. It rarely happens as a sudden “enlightenment”. It happens when you integrate your different dimensions, which is what becoming an adult is all about. To be successful, a psychologically mature person must be able to handle ambiguity, sustain the tension of opposites, thereby allowing the underlying complexity to arise. In other words, individuation can better take shape where there is an open spectrum of possibilities.

Individuation is a challenging process because we are usually burdened with a lot of baggage. Carl Jung suggested that the greatest burden children must bear is the unlived life of their parents. The failed individuation of a parent is transmitted to the children in the form of either a repetition on the parents’ lives or overcompensation in the opposite direction.

With the midlife crisis comes a sensation of loss of meaning, because the pain of inauthenticity generates intense suffering. DVCs generally experience it early. In any case their quest for meaning gives them a strong incentive to know more about themselves.

How to choose activities among so many

DVCs’ main problems are their inability to make choices and their inconstancy when they do manage to choose. Therefore finding ways to choose and sticking to those choices is essential. Lospennato suggests doing the following:

List everything you’d like to do: ignore money or other constraints, just list everything you’d like to do or experience (in verbal phrases). Your “inventory of dreams” can be done over the course of a few days.

Rank the items in the inventory based on three questions:- a. How badly do I want this?;

- b. How talented am I to do it?;

- c. How can it be monetised? The answer to each question is a grade, which will serve to rank the items.

- Weigh in the learning curves of the activities and the level you want to achieve: you can be an amateur, a semi-professional, a full-time professional or a researcher on the subject. It will largely determine your chances of monetisation.

At some point, you will be able to find the sweet intersection between wishes, talents and money, where you should focus most of your effort.

The sweet spot is where all the professional opportunities should be found. But naturally other activities can also be pursued as amateurs. To express multiple talents and find fulfillment, DVCs need to find the right balance between their different activities.

There is a difficult trade-off between focus and balance. Focus means investing all your energy and attention into one thing whereas balance means distributing that energy and attention among different things. For DVCs finding the right balance is particularly challenging and essential. For them less is always more. When choosing how to spend their time and energy, they should always do less than they’d like to.

How to get your priorities straight

It you never have the time to do all the items on our to do lists, it might be because you don’t know how to make those lists in a clever way. It is critical to use criteria to evaluate all the pendings on those lists. Priority is a combination of urgency and importance. Sadly our modern lives are full of unimportant urgencies.

Emergencies, i.e. situations that present a clear and present danger to us or other people, require the suspension of all other non-critical pendings. But they are very rare. Most of the time, we are drowned in everyday urgent but non-important stuff, and devote too little time to important non-urgent things. As for non-urgent unimportant items, they’re the trivia that shouldn’t even be on the list.

When it comes to setting your priorities straight, here are the right attitudes to adopt:

- Do not work with an artificial sense of urgency;

- Forget the “wow!” factor and do not try to amaze people all the time;

- Decide a way to go and when possible stick to it;

- Do not use the saved up time to work more. Saved time must be spent wisely and immediately.

Don’t let narcissism get in the way

Narcissism is natural and even healthy…up to a point. It can become pathological when it leads to a constant oscillation between arrogance and self-hate. Signs of an overly narcissistic personality include:

- Hypersensitivity to criticism;

- A grandiose sense of entitlement that is never satisfied;

- A false sense of superiority (nothing is ever difficult);

- An undue sense of shame generated by the non-achievement of unrealistic goals;

- Extreme panic at the idea of a challenge.

Extreme narcissism becomes dangerous “when your fantasy self writes checks that your real self cannot pay”. It can lead to addiction, depression, or drug abuse. Your “normal” DVC grandiosity can be confronted with:

- Real relationships with real people;

- Less “bitchin’ and moanin’” about everything;

- Abandoning the quest for perfection;

- Accepting failure.

Illustration: Pablo Grand Mourcel

More inspiration: Laetitia Vitaud

Future of work author and speaker

How women over 50 are reinventing their careers and the future of work

Women in their 20s struggle to be taken seriously, while middle-aged women battle discrimination... So how are women over 50 reinventing the wheel?

Apr 02, 2024

Ego depletion: The more decisions you make, the worse they become!

Digital demands and information overload are at an all-time high, making decision fatigue a critical challenge impacting productivity and well-being.

Mar 27, 2024

Let's stop looking down on ‘good students’ at work

Much like the adjective “kind”, calling someone a “good student” in the workplace is almost always pejorative, but why?

Feb 22, 2024

Is a world without work (really) possible?

Our Lab expert Laetitia Vitaud explains why she doesn’t believe in a future of unemployment and leisure.

Feb 19, 2024

Working time: It’s not just a question of how long you spend

If we look back to the works of the ancient Greeks, we begin to see that time isn’t just about “duration.” Intrigued?

Jan 08, 2024

Inside the jungle: The HR newsletter

Studies, events, expert analysis, and solutions—every two weeks in your inbox